Description

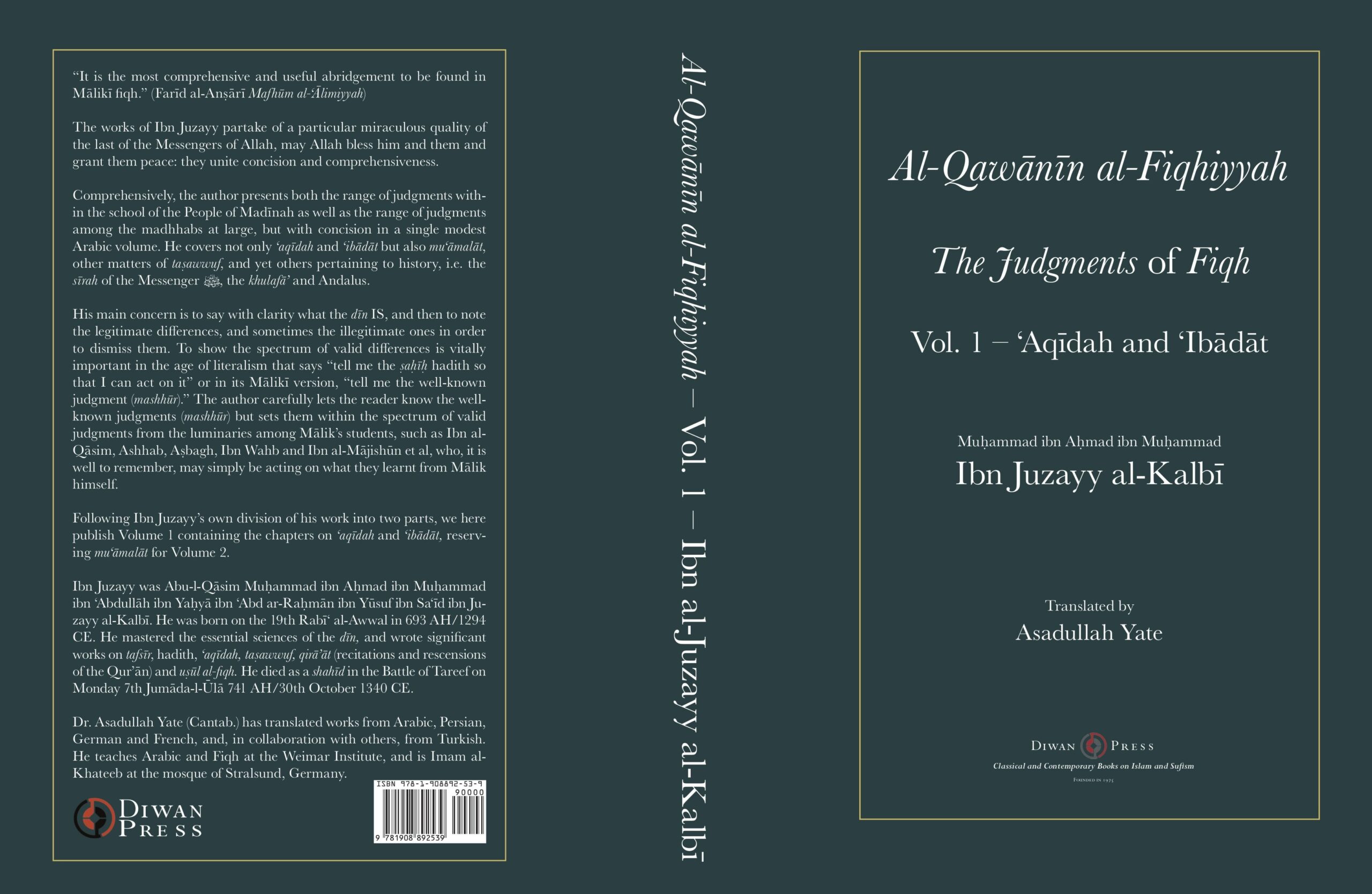

“It is the most comprehensive useful abridgement to be found in Mālikī fiqh.” (Farīd al-Anṣārī, Mafhūm al-‘Ālimiyyah)

The works of Ibn Juzayy, including his tafsīr and this work of fiqh, partake of a particular miraculous quality of the last of the Messengers of Allah, may Allah bless him and them and grant them peace: they unite concision and comprehensiveness. He said a, “I was given concise comprehensive speech (jawāmi‘ al-kalim).” (Al-Bukhārī (7013) and Muslim (523)). The comprehensive character of this book is evident enough in that the author presents both the range of judgements within the school of the People of Madīnah as well as the range of judgments among the madhhabs at large, something ordinarily encompassed in multi-volume tomes by erudite scholars, but here achieved with concision in a single modest Arabic volume. It is comprehensive also in covering not only ‘aqīdah and ‘ibādāt, in volume 1 of our translation, but also mu‘āmalāt, and other matters ordinarily regarded as being under the rubric of taṣawwuf, and yet others pertaining to history, i.e. the sīrah of the Messenger a, the khulafā’ and Andalus, in volume 2.

Moreover, the author escapes entirely the trap that lies in wait for such an ambitious project: the cleverness that dazzles but confuses. His main concern is to say with clarity what the dīn IS, and then to note the legitimate differences, and sometimes the illegitimate ones in order to dismiss them. To show the spectrum of valid differences is vitally important in the age of literalism that says “tell me the ṣaḥīḥ hadith so that I can act on it” or in its Mālikī version, “tell me the well-known judgment (mashhūr).” The author carefully lets the reader know the well-known judgment (mashhūr) but sets it within the spectrum of valid judgments from the luminaries among Mālik’s students, such as Ibn al-Qāsim, Ashhab, Aṣbagh, Ibn Wahb and Ibn al-Mājishūn et al, who, it is important to remember, may have been acting on and speaking by what they learnt from Mālik, unless, as with the case of Ibn al-Qāsim in the Mudawwanah when he specifically says on occasion that he heard nothing from Mālik about an issue but his own opinion is such-and-such.

Lastly the work has another quality, which it shares with the Risālah of Ibn Abī Zayd al-Qayrawānī, and which is easy enough to overlook: the narrative quality of someone who is recording what he knows rather than laboriously researching in various learned tomes and then writing down his results.

Ustādh Farīd al-Anṣārī wrote about it:

The book al-Qawānīn by Ibn Juzayy, may Allah have mercy on him, has been done a great injustice, as was also the case with the Muwāfaqāt of ash-Shāṭibī, since it did not become known well enough to be studied in madrasahs until the last century, whereas other summaries have acquired precedence in Mālikī fiqh, even though they do not rise to the level of the Qawānīn in terms of knowledge. This abridged compilation of Mālikī fiqh is distinguished by qualities that others in the history of the madhhab do not possess.

What the author himself says in introduction to this book of his is enough, when he said, may Allah have mercy on him:

“Know that this book is superior to other books by virtue of three qualities:

1. It combines a clear arrangement of the madhhab with mention of the differences with the other madhhabs – contrary to other books which deal with the madhhab in particular or with the differences with other madhhabs in particular;

2. We have laid it out with clarity by dividing it up and arranging it elegantly and we have facilitated its understanding by pruning it of any superfluities or defects and clarifying the way it is expressed – so how many divisions within sections and how many detailed expositions of primary judgements have facilitated an understanding of what was difficult and made the exceptional, anomalous judgements more accessible!

3. In it we have aimed to combine concision and explanation, despite the fact that they are rarely to be found in combination, and thus by the help of Allah it turned out to contain an ease of expression, to be subtle in its indications, complete in its meanings, but with so few words that those wishing to learn it by heart become devoted to it.”

He told the truth ﷺ, for all of these distinguishing qualities and more are to be found in the Qawānīn. It is the most comprehensive useful abridgement to be found in Mālikī fiqh, along with its drawing comparisons and parallels with the major madhhabs to such an extent that one of them said that it is an abridgement of the Bidāyat al-Mujtahid, but that is not correct, since its contents, in terms of derivative rulings, exceed those of the aforementioned book by a great deal. On the contrary, it is an abridgement of a great variety of books, and in terms of the methodological approach there is no relationship between the two books. (Farīd al-Anṣārī, Mafhūm al-‘Ālimiyyah)

This book was not written in a library as part of a private conversation among scholars, with their agreements, disagreements and disputes, but was written by a man of knowledge engaged in living the dīn and acting by it, and will only be of benefit to people who take it on the same terms. May Allah make it of benefit to Muslims new and old, in the East and the West, in a new age for the dīn.

Diwan Press are publishing this important work in two volumes: Vol.1 on ‘Aqīdah and ‘Ibādāt, and Vol.2 on Mu‘āmalāt and miscellaneous matters.

Vol. 1:

15.6 x 23.4 cm. 385 pages

Abu-l-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Juzayy al-Kalbī from Granada in Andalusia was born in 693 AH into a distinguished and noble family and died shahīd at the great battle of Tareef in 741 AH. He was a qāḍī, grammarian, faqīh, commentator on the Qur’ān and poet. Among his teachers were Ibn az-Zubayr, Ibn Rashīd, Qāḍī Ibn Bartāl, the khaṭīb at-Tanjalī and Abu-l-Qāsim ibn Shāt. Among his works are Wasīlah al-muslim fi tahdhīb Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, al-Aqwāl as-sunniyyah fi kalimāt as-sunniyyah, Taqrīb al-wuṣūl ilā ‘ilm al-uṣūl, an-Nūr al-mubīn fī qawā‘id ‘aqā’id ad-dīn, Taṣfiyyah al-qulūb fī wuṣūl ilā ḥaḍrah ‘allām al-ghuyūb, al-Mukhtaṣar al-bāri‘ fi qirā’ah Nāfi‘ and his Tafsīr kitāb at-tas-hīl li ‘ulūm at-tanzīl.

His son, Abū Abdullah Muḥammad ibn Juzayy al-Kalbī (d. 758 AH), the scribe of the Riḥlah of Ibn Battuta, is sometimes confused with him.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.